"You are being very unreasonable, my love," Lady Brampton had complained.

Rosalind had reached into her reticule and withdrawn her vinaigrette, glaring meaningfully at her brother. "There is always Margaret Wells," she had said.

Brampton had laughed. "Yes, I suppose there is always Margaret Wells," he had agreed.

"Really, Richard," Rosalind had continued crossly, "she is a very respectable female. It is true that she never really took with the ton, but I do believe it was her good sense and proper manner that frightened away any would-be suitors. She would make an eminently suitable wife, I am sure. True, her father is neither titled nor wealthy, but he is of impeccable lineage and manages to maintain a country estate as well as a town house. I hear they are even planning a Season for the younger girl, Charlotte."

"Margaret Wells. Is she the sweet little lady who has taken to sitting with the chaperones at assemblies? And has donned caps?" Lady Brampton had asked.

And somehow, he was never to know quite how, Brampton had found himself drawn inextricably into the scheme. Lady Brampton had renewed her old acquaintance with Mrs. Wells; the Earl of Brampton had joined a card table at White's Club with Mr. Wells one evening and had waited on him the next day to propose a marriage contract with his daughter.

Brampton, reclining now in his library, raised his glass to his eye. Strange! Brandy was dark brown, was it not, not transparent? And when you turned the glass upside down, was not the liquid supposed to pour out? His sluggish brain finally reached the inevitable conclusion: the glass must be empty! "At least I am not quite drunk," he sighed with relief as he pulled himself out of his chair and tried to steer the shortest course to the desk. The glass refilled, Brampton somehow found his way back to the sanctuary of the chair and sank into it.

Well, the deed was done. He was affianced, and according to the code of gentlemanly ethics by which he lived, there was no possible way of turning back now. He was doomed to having that dull and unattractive woman living permanently in his home. He was going to have to visit her bed regularly each night. I shall have to hope that she proves fertile and I potent, he thought in despair. Once she begins to increase, at least I shall be spared that ordeal. Until the next time around, that is.

His thoughts passed sluggishly, but by a natural progression, to Lisa. He wished that he had not drunk so much. It might have helped now to drive to the little house in which he had set her up three months ago in a discreet area of London, and bury his sorrows and misgivings in her soft and ample and very feminine body. He thought longingly of her thick, blond hair and her tantalizingly rouged cheeks and full lips, of her heavy breasts, narrow waist, and ample hips, of her nimble, roving fingers.

He dragged his mind away. Not tonight! He could not even drag up enough desire to make the thought process worthwhile. At least in the future he would have Lisa to satisfy his sexual appetite while duty forced him to use his wife to procure the succession.

Brampton's head drooped. He began to snore heavily at about the same moment as his half-filled brandy glass slipped from his nerveless fingers and spilled its contents over his library carpet.

Margaret Wells was still awake. She had retired to her room as soon as Lord Brampton had returned her and her mother to their home after the opera. Kitty, her lady's maid, had undressed her, brushed and braided her hair, brought her a cup of steaming chocolate, and snuffed the candles before she left. For a couple of hours Margaret had tossed and turned, trying to still her churning thoughts, trying to induce sleep. But by now she had accepted the fact that she would not sleep, and lay quietly on her back, hands propped behind her head on the pillow, staring at the rust-colored velvet hangings above her head.

She was not quite sure whether she was in the middle of a rapturous dream or a ghastly nightmare. All she did know was that suddenly, with only one day's warning, she was betrothed to the man she had loved passionately and hopelessly for six years. Her mind could still not grasp the fact as reality. When Papa had warned her the day before that Richard Adair, Earl of Brampton, was to come the next day to pay his addresses to her, Margaret had felt a sick lurching of her stomach. How had her father discovered her feelings? What sort of a sick joke was he playing on her?

And when she had sat across from the earl that afternoon, she had had to use all her willpower to put into practice the training of her youth-to sit quietly poised before him, not betraying her feelings by so much as a tremble in her hands or a softening of her lips. But she had had to look up at him now and again to convince herself that he really was there. She had not needed the evidence of her eyes when he had taken her hand in his. All her feelings had come to the fire and she had had great difficulty controlling her voice when his lips had brushed her hand for a brief moment.

Margaret had had a quiet childhood and a strict upbringing. Her father was not a wealthy man. He had kept his family at his estate in Leicestershire most of the time, taking them to London only occasionally. Her mother was a quiet and sober woman; she had instilled these virtues in her daughter. When Margaret's only sister had been born seven years after her, Margaret had been expected even more to set an example as the older sister. And she had learned her lesson well. No one knew, except perhaps Charlotte, who loved her sister so deeply that she saw beyond the outer facade, that Margaret was a woman with passion and deep feelings, who longed to be gay and adventurous. All signs of the real Margaret were fiercely repressed.

Her parents had taken her to London for her come-out when she was eighteen. Although not wealthy, Mr. Wells was accepted unquestioningly by the ton; Margaret, therefore, had soon been caught up in the whirl of balls, routs, soirees, and other entertainments with which the ton occupied their time. And she had loved every moment of it. Although her public image was the quiet one which she had been trained to project, she had not lacked either for female friends or for male admirers. She had not exactly taken the ton by storm, but her trim little figure, her heart-shaped face with the large, quiet gray eyes framed by long, dark lashes, and her sweet mouth had made her a pleasing attraction.

That had all been before the night of the Hetheringtons' masquerade ball, two months after her come-out. The chance to attend a masquerade was rare; the regular masquerade balls held at the opera house were considered unsuitable for the girls of the ton. They were noisy, rather ribald affairs. Consequently, invitations to the Hetheringtons' ball had been coveted and the event had developed into a great squeeze. Fortunately, the day had been unseasonably warm for April. The garden had been decked with lanterns so that the crowd had been able to spill out into the outdoors away from the stuffy ballroom.

Margaret had been dressed as Marie Antoinette, her wide-skirted silver dress and powdered wig hired for the occasion, a silver mask covering her whole face except her eyes, mouth, and jawline. She had been excited. Somehow, knowing that she was disguised almost beyond recognition, she had felt as if she could throw away the restraints that were normally second nature to her. She had danced and laughed and talked, lowering the tone of her voice and assuming a French accent. Her behavior had become even more animated when she had realized that both her mother and her father had disappeared into the card room.

And then she had seen the Earl of Brampton. He had been unmistakable, his tall, broad-shouldered figure clothed in a black domino, a glimpse of blue satin coat and knee breeches, snowy white neckcloth and stockings beneath, his rather long dark hair waving back from his face, a token black mask covering his eyes. Margaret's heart had missed a beat even before she had realized that those eyes were fixed steadily on her as she sipped her lemonade and chatted animatedly to the flushed young man beside her.

Margaret had seen Brampton before at various assemblies and had a schoolgirlish infatuation for his handsome, romantic figure. He was older than she, and she had very sensibly concluded that he was beyond her touch. She would be content to worship from afar. But now, seeing his eyes still on her, she had flirted her fan daringly in his direction and turned her back on him, swinging the wide skirt with her hips as she did so.

One minute later she had felt a hand on her arm. "Will you do me the honor of dancing the next waltz with me, mademoiselle?" his low voice murmured seductively into her left ear.

Margaret had pretended to consult her little engagement booklet. "But yes, monsieur," she had replied, with theatrical accent intact, "I see that the next waltz is free."

He had laughed, outrageously interlaced his fingers with hers, and led her onto the floor, leaving the flushed young man gaping behind them.

"I hope you have been granted permission by one of the patronesses of Almack's to waltz, my little French angel," he had said, "or there will be scandal for you at unmasking time."

"But yes, of course," she had replied, tossing her head, "I have been permitted since this age ago."

He had laughed again and moved her into the dance, holding her a little too close for strict propriety. The tips of her breasts had touched his blue coat on two separate occasions as he had whirled her into a turn, doing nothing for her equilibrium. She had never been this close to a man before.

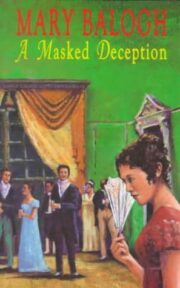

"A Masked Deception" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Masked Deception". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Masked Deception" друзьям в соцсетях.