There was an endless gallery lined with serious-looking family portraits, a gigantic living room with a magnificent chandelier, a library lined with miles of ancient books, a music room with two harps and a grand piano, a dining room with a table long enough to seat forty people for the dinner parties they used to give. The reception rooms seemed to go on forever, until they finally reached a small, cozy drawing room where her ladyship liked to sit and gaze out at the gardens. As Annabelle looked at the surroundings, and the splendor of the home, it was hard to believe that anyone who had grown up here could rape a woman, and then threaten to kill her if she told. There were photographs of both the Winshire sons on the mantelpiece in the room where they were sitting. And after they had tea with scones and clotted cream and jam, Lady Winshire asked one of the maids to show Consuelo the stables. She had arranged for a pony to be brought around, if she wanted to try and ride it, and Annabelle thanked her for her kindness to them, and her warm welcome as Consuelo disappeared to see the pony.

“I have a lot to make up for,” the older woman said simply, and Annabelle smiled. She didn’t hold her responsible for her son’s crimes. And how could they be considered crimes when they had resulted in Consuelo, no matter how she had happened. She said as much to Lady Winshire, who thanked Annabelle for her generosity of spirit, and said her son didn’t deserve it, much as she had loved him. She confessed sadly that he had been wild and spoiled.

They chatted for a while and strolled in the gardens, and in a little while, one of the grooms appeared, leading Consuelo on the pony. She looked ecstatic. It was clear that the child was having a ball, thanks to her newfound grandmother. Lady Winshire asked if Annabelle would like to ride too. She said she hadn’t in years, but might do so the next morning. All of those luxuries and indulgences had gone out of her life when she left the States. It would be fun, Annabelle thought, to ride again. She had done a lot of it in her youth, mostly in Newport in the summer.

After Consuelo and the groom went back to the stables, Annabelle mentioned that she was thinking of selling her house in Newport.

“Why would you sell it?” the older woman asked, with a look of disapproval. “You said it had been in your family for generations. You need to preserve it, if it’s part of your history. Not sell it.”

“I’m not sure I’ll ever go back. I’ve been gone for ten years. It’s just sitting there, unloved and empty, with five servants.”

“You should go back,” Lady Winshire said firmly. “That’s part of Consuelo’s history too. She has a right to that, yours, ours, it’s all part of who she is, and who she’ll become one day. Just as it’s a part of you.” Clearly, all of that hadn’t helped Harry, Annabelle thought to herself, but she wouldn’t have said it to his mother, who knew it anyway, and had said as much herself. “You can’t run away from who you are, Annabelle. You can’t deny it. And Consuelo should see it. You should take her back to visit sometime.”

“That’s all over for me,” Annabelle said, looking stubborn as Lady Winshire shook her head.

“It’s only beginning for her. She needs more than Paris in her life, just as you do. She needs all our histories blended together, and offered to her like a bouquet.”

“I’ve had a very good offer. I could always buy a property in France.” She never had, though. All she had was her very modest house in the sixteenth arrondissement. She had nothing in the country, and she had to agree, seeing Consuelo here, it was doing her good.

“I suspect you can do that anyway,” her ladyship guessed correctly. Annabelle had inherited a very large fortune from her father, and an only slightly smaller one from her mother, and she had hardly spent anything in years. It was no longer in keeping with her lifestyle, or her life as a doctor, and she had been careful not to let any of that show for the past ten years. It spoke well of her, but now, at almost thirtytwo, she was old enough to enjoy it.

Lady Winshire turned to her with a smile then. “I hope you’ll both come to visit often. I still go to London once in a while, but most of the time I’m here.” It had been her late husband’s family seat, which had brought her to another thought she had wanted to mention to Annabelle, when Consuelo wasn’t around. She wasn’t sure if it was too soon to mention it, but it had been much on her mind. “I’ve been thinking a great deal about Consuelo’s situation, because you and her father were never married. That could be a heavy burden for her to carry in a few years, as she gets older. You can’t lie to her forever, and one day someone may figure it out. I spoke to our attorneys, and it makes no sense for me to adopt her, and she’s your daughter. Harry can’t marry you posthumously, which is unfortunate. But I can officially recognize her, which would improve things somewhat, and she could add our name to yours, if that would be acceptable to you,” she said cautiously. She didn’t want to offend the child’s mother, who had been so brave about shouldering all her responsibilities alone. But Annabelle was smiling at her. She had become more sensitive to it herself, ever since Antoine’s outrageous insults, especially calling Consuelo a bastard. The thought of it still hurt her now.

“I think that’s a lovely idea,” Annabelle said gratefully. “It might make things easier for her one day.”

“You wouldn’t mind?” Lady Winshire looked hopeful.

“I’d like it very much.” She associated Lady Winshire with the name, and not her evil son. “That would make her Consuelo WorthingtonWinshire, or the reverse, whatever you prefer.”

“I think Worthington-Winshire would do very well. I can have our attorneys draw up the papers whenever you like.” She beamed at Annabelle, who leaned over and hugged her.

“You’ve been very kind to us,” Annabelle said gratefully.

“Why wouldn’t I be?” she said gruffly. “You’re a good woman. I can see what a wonderful mother you’ve been to her. Somehow, in spite of everything, you’ve managed to become a doctor. And from what I’ve been told, you’re a good one.” Her own physician had discreetly checked, through connections he had in France. “In spite of what my son did to you, you’ve recovered, and you don’t hold it against the child, or even against me. I’m not even sure you hold it against him, and I’m not sure I could have done that in your place. You’re respectable, responsible, decent, hard-working. You worked like a Trojan during the war. You have no family behind you. You’ve done it all on your own, with no one to help you. You were brave enough to have a child out of wedlock and make the best of it. I can’t think of a single thing about you not to respect or like. In fact, I think you’re quite remarkable, and I’m proud to know you.” What she said brought tears to Annabelle’s eyes. It was the antidote to everything Antoine had said.

“I wish I could see it the way you do,” Annabelle said sadly. “All I see are my mistakes. And all people seem to see, except for you, are the labels others have put on me.” She confessed one of her darkest secrets then, and told her she had been divorced before she left the States, and told her why. It only made Lady Winshire admire her more.

“That’s quite an amazing story,” she said, thinking about it for a moment. She wasn’t easily shocked, and the story of Annabelle’s marriage to Josiah only made her feel sorry for Annabelle. “It was foolish of him to think he could pull it off.”

“I think he believed he could, and then found he couldn’t. And his friend was always close at hand. It must have made it even more difficult for him.”

“People are such fools sometimes,” Lady Winshire said, shaking her head. “And it was even more foolhardy of him to think that divorcing you wouldn’t blacken your name. It’s all very nice to say he was trying to free you up for someone else. Divorcing you for adultery in order to do it only threw you to the wolves. He might as well have burned you at the stake in a public place. Really, men can be so ignorant and selfish at times. I don’t suppose you can undo that very easily now.” Annabelle shook her head. “You just have to tell yourself that you don’t care. You know the truth. That’s all that matters.”

“It won’t stop people from slamming their doors in my face,” Annabelle said wistfully. “And Consuelo’s.”

“Do you really care about those people?” Lady Winshire asked honestly. “If they’re mean-spirited enough to do that to you, and to her, then they’re not good enough for either of you, rather than the reverse.” Annabelle told her about her recent experience with Antoine then, and she was outraged. “How dare he say things like that to you? There is nothing more small-minded and downright vicious than the self-righteousness of the so-called bourgeoisie. He would have made you miserable, my dear. You were quite right not to let him come back. He wasn’t worthy of you.” Annabelle smiled at what she said, and had to agree. She was sad about what had happened, but once she had discovered who Antoine was, she didn’t miss him. She just missed the dream of what she had hoped they would have, but clearly never would. It had been an illusion. A beautiful dream that turned into a nightmare with his ugly words and assumptions. He was far too willing to believe the worst of her, whether true or not.

Consuelo came bounding into the room then, excited about all the horses she had seen in the barn, and the ride on the pony. And she was even more so when she saw her room. It was a big, sunny chamber, decorated in flowered silks and chintz, and it adjoined her mother’s room, which was more of the same. And that night at dinner, they told her about her new double name.

“It sounds hard to spell,” Consuelo said practically, and both her mother and grandmother laughed.

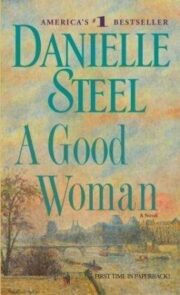

"A Good Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Good Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Good Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.