It took them three hours through back roads to get to the hospital. The roads were in bad shape and deeply rutted, with potholes everywhere. No one had time to fix them, and there were no men to do it. Every able-bodied man was in the army, and there was no one left at home to do repairs or maintain the country, except old people, women, children, and the wounded who had been sent home. Annabelle didn’t mind the rough roads as they bounced along in Jean-Luc’s truck, which he told her he normally used to deliver poultry. She smiled when she saw that there were feathers stuck to her valises. She found herself looking down at her hands for a moment, to make sure her nails were cut short enough, and saw the narrow ridge that her wedding band had left. Her heart ached for a minute. She had taken it off in August and still missed it. She had left it in the bank vault in a jewel box, with her engagement ring, which Josiah had insisted that she keep. But she had no time to think of that now.

It was just after nine when they reached the Abbaye de Royaumont, a thirteenth-century abbey, in slight disrepair. It was a beautiful structure with graceful arches, and a pond behind it. The Abbey was bustling with activity. There were nurses in uniforms pushing men in wheelchairs in the courtyard, others hurrying into the various wings of the building, and men being carried on stretchers out of ambulances driven by women. The stretcher-bearers were female too. There were nothing but women working there, including the doctors. The only men she saw were injured. After a few minutes, she saw one male doctor rushing into a doorway. He was a rarity in a vast population of women. And as she looked around, not sure where to go, Jean-Luc asked if she wanted him to wait for her.

“Yes, if you don’t mind,” she said, overwhelmed for a minute, but well aware that if they didn’t allow her to volunteer, she had no idea where to go or what else to do. And she was determined to stay in France and work there, unless she went to England and volunteered. But whatever happened, she wasn’t going home. Not for a long time anyway, or maybe ever. She didn’t want to think about that now. “I have to talk to the people in charge and see if they’ll keep me,” she said softly. And if they did allow her to work, she would need a place to stay. She was willing to sleep in a barracks or a garage if she had to.

Annabelle walked across the courtyard, following signs to various parts of the makeshift hospital set up in the Abbey, and then she saw an arrow pointing toward some offices under the arches, which said “Administration.”

When she walked in, there was a fleet of women lined up at a desk, handling paperwork, as female ambulance drivers handed requisition slips to them. They were keeping records on everyone they treated, which wasn’t always true at all the field hospitals, where in some cases they were under far more pressure. Here, there was a sense of frenzied activity, but at the same time clarity and order. The women at the desk were French for the most part, although Annabelle could hear that some of them were English. And all of the ambulance drivers were young French women. They were locals who had been trained at the Abbey, and some of them looked about sixteen. Everyone had been pressed into service. At twenty-two, Annabelle was older than many, although she didn’t look it. But she was certainly mature enough to handle the work if they let her, and far more experienced than most volunteers.

“Is there someone I should speak to about volunteering?” Annabelle asked in flawless French.

“Yes, me,” said a woman of about her own age, smiling at her. She was wearing a nurse’s uniform, but was working at the desk. Like everyone else, she was doing double shifts. Sometimes the ambulance drivers, or doctors and nurses in the operating theaters, kept on for twenty-four hours straight. They did what was needed. And the atmosphere was pleasant and cheerful and energetic. Annabelle was impressed so far.

“So what can you do?” the young woman at the desk asked her, looking her over. Annabelle had pinned her apron on, to look more official. In the serious black dress she looked like a cross between a nurse and a nun, and was in fact neither.

“I have a letter,” Annabelle said nervously, fishing it out of her purse, worried that they would reject her. What if they only took nurses? “I’ve done medical work since I was sixteen, volunteering in hospitals. I worked at Ellis Island in New York for the last two years, with immigrants, and I’ve had quite a lot of experience dealing with infectious diseases. Before that, I worked at the New York Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled. That might be a little more like what you’re doing here,” Annabelle said, sounding both breathless and hopeful.

“Medical training?” the woman in the nurse’s uniform asked as she read over Annabelle’s letter from the doctor on Ellis Island. He had praised her highly, and said that she was the most skilled untrained medical assistant he had ever encountered, better than most nurses and some doctors. Annabelle had blushed herself when she read it.

“Not really,” Annabelle said honestly about her lack of training. She didn’t want to lie to them, and pretend that she knew things she didn’t. “I’ve read a lot of medical books, particularly about infectious diseases, orthopedic surgery, and gangrenous wounds.” The nurse nodded, looking her over carefully. She liked her. She looked anxious to work, and as though it meant a lot to her.

“That’s quite a letter,” she said admiringly. “I take it you’re American?” Annabelle nodded. The young woman was British but spoke perfect French, without a trace of accent, but Annabelle’s French was good too.

“Yes,” Annabelle said in answer to the question about her nationality. “I arrived yesterday.”

“Why did you come over?” the nurse asked, curious, as Annabelle hesitated, and then blushed with a shy smile.

“For you. I heard about this hospital from the doctor on Ellis Island, who wrote the letter. It sounded wonderful to me, so I thought I’d see if you could use some help. I’ll do anything you ask me. Bedpans, surgical bowls, whatever.”

“Can you drive?”

“Not yet,” Annabelle said sheepishly. She had always been driven. “But I can learn.”

“You’re on,” the young British nurse said simply. There was no point putting her through the mill with a letter like that, and she could see that Annabelle was a good one. Her face burst into a broad smile as the woman behind the desk said it. This was exactly what she had come for. It had been worth the long, lonely, frightening trip to get here, despite minefields and U-boats, and her own fears after the Titanic. “Report to Ward C at thirteen hundred hours.” It was in twenty minutes.

“Do I need a uniform?” Annabelle asked, still beaming.

“You’re fine as you are,” the woman said, glancing at her apron. And then she thought of something. “Do you have a billet? A place to stay, I mean.” They exchanged a smile.

“Not yet. Is there a room I could have here? I can sleep anywhere. On the floor if necessary.”

“Don’t say that to anyone else,” the nurse warned her, “or they’ll take you at your word. Beds are in short supply here, and anyone will be happy to take yours. Most of us are hot bunking, we switch off in the same beds with people who work different shifts. There are a few left in the old nuns’ cells, and there’s a dormitory in the monastery, but it’s pretty crowded. I’d grab one of the cells if I were you, or find out if someone will share one. Just go over and ask around. Someone will take you in.” She told her what building they were in, and in a daze, Annabelle went out to find Jean-Luc. Her mission was a success, they were going to let her work there. She could hardly believe her good fortune, and she was still smiling when she found Jean-Luc standing next to his poultry truck, as much to protect it as so that she could find him. Vehicles were in short supply, and he was terrified someone would take it from him, and commandeer it as an ambulance.

“Are you staying?” he asked her, as she walked up to him, smiling.

“Yes, they took me,” she said, relieved. “I start work in twenty minutes and I still have to find a room.” She reached into the back of the truck, brushed the chicken feathers off her valises, and pulled them out. He offered to carry them for her, but she thought she’d best do it herself. She thanked him again, and had already paid him that morning. He gave her a warm hug, kissed her on both cheeks, wished her luck, and got back in his truck and left.

Annabelle walked into the Abbey carrying her bags, and found the area where the nurse had told her the old cells were. There were row upon row of them, dark, small, damp, musty, and they looked miserably uncomfortable, with one lumpy mattress on the floor of each, and a blanket, and in many cases no sheets. Only a few of the cells had sheets, and Annabelle suspected correctly that the women who lived in those cells had provided them themselves. There was one communal bathroom to about fifty of the cells, but she was grateful to have indoor plumbing. The nuns had clearly not lived in any kind of comfort or luxury, in the thirteenth century or since. The Abbey had been purchased from their order many years before, at the end of the last century, and had been privately owned when Elsie Inglis took it over and turned it into a hospital. It was a beautiful old building, and although not in fabulous condition, it suited their purpose to perfection. It was an ideal hospital for them.

As Annabelle looked around, a young woman came out of the cells. She was tall and thin and looked very English, with pale skin, and hair as dark as Annabelle’s was blond. She was wearing a nurse’s uniform, and she smiled at the new arrival with a rueful expression. She looked like a nice girl. There was an instant affinity between the two women.

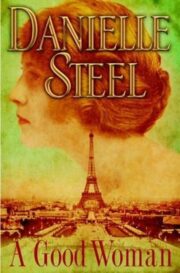

"A Good Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Good Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Good Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.