There were dances, and there were forfeits and still more dances. There were tables laden with cake, negus, a great piece of cold roast, a great piece of cold ham, and mince pies. Plenty of beer flowed throughout the night. But the greatest event of the evening came after the roast, when the fiddler struck up “Sir Roger de Coverley.” Then, old Peterson stood up to dance with Mrs. Peterson. Four and twenty pair of partners joined in—people who were not to be trifled with, people who would dance and had no notion of walking, including Darcy.

But if they had been twice as many, old Peterson would have been a match for them and so would Mrs. Peterson.

The Spirit noticed this and said to Darcy, “She was worthy to be his partner in every sense of the term. If that is not high praise, tell me what is higher and I will use it.”

“Indeed,” Darcy observed from the sidelines, “all of the couples were well matched. Oh, the women laughed and flirted and danced with the students, but it was clear that they were just having an evening’s fun. They were truly happy with their own partners.”

When the clock struck eleven, the domestic ball broke up. Mr. and Mrs. Peterson took their stations, one on either side of the door, and shaking hands with every person individually as he or she went out, wished him or her a Merry Christmas. Everybody had retired but Darcy and his friend, so they did the same to them; and thus the cheerful voices died away, and the lads were left to find their way back to their rooms.

During the whole of this time, Darcy had acted quite unlike himself. His heart and soul were in the scene and with his former self. He corroborated everything, remembered everything, and enjoyed everything. It was not until now, when the bright faces of his former self and Dick were turned from them, that he remembered the Ghost and became conscious that it was looking full upon him.

“Were you not bored?” asked the Ghost, as they followed the young men.

“Bored?” echoed Darcy.

“I should think you would be,” answered the Spirit, “at an assembly such as that, with people of little character and no breeding. Cooks and milkmen, housemaids and bakers?”

“It was not the company,” said Darcy, heated by the remark, and speaking unconsciously like his Cambridge self. “Peterson could not bear to see anyone unhappy. The happiness he gave was to all who needed it, especially to those who were alone during the holidays; it mattered not if you were a Duke or a dust boy. All mingled at the Fuzzy Whig. Pretensions were not allowed.”

He felt the Spirit’s glance and stopped.

“What is the matter?” asked the Ghost.

“Nothing particular,” said Darcy.

“Something, I think,” the Ghost insisted.

“No,” said Darcy. “No. I should like to have behaved better at an assembly I attended in Meryton. That’s all.”

His former self turned down the lane as he gave utterance to the wish; and Darcy and the Ghost again stood side-by-side, alone in the open air.

“My time grows short,” observed the Spirit. “Quick!”

The address was again familiar to Darcy, a small house in an exclusive section of London. Darcy saw himself. He was older now. It was the Christmas dinner of a year ago. He was not alone, but sat across from a red-headed woman in a green dress. He was embarrassed that his mother should see him here.

“It matters little,” she said softly. “Very little. Another has displaced me; and if she can cheer and comfort you in the time to come, as I have tried to do, I have no just cause to grieve.”

“Who has displaced you?” he rejoined.

“I know not, but you have not been the same since you came back from Hertfordshire.”

“You are mistaken,” he said. “There is no-one!”

“Are you trying to convince me or yourself?” she asked gently.

“There is no-one,” he repeated. “I am not changed towards you.”

She shook her head.

“Am I?”

“Our friendship is an old one. It was made when we were both in need of comfort and companionship. You were still grieving for your father and I was not grieving for my husband. Still, I had much to recover from.”

“He was not a gentleman,” he said quietly.

“True,” she returned. “Marriage, that which promised happiness when I was young, was fraught with misery. I learned that a parent does not always know what is best for their child. A fine name, good income, and a grand home will never make up for a lack of character in its owner.” She hesitated a moment before continuing. “I am not the child I was upon my marriage nor am I the pathetic creature that I was after it was over. You helped me more than I can ever acknowledge nor can I sufficiently express my gratitude.”

“Gratitude was never necessary,” replied Darcy.

“I know that it is not, but it is what I feel. It is with much thanks that I release you.”

“Have I sought release?”

“In words? No. Never.”

“In what then?”

“In a changed nature; in an altered spirit; the atmosphere of another who is ever on your mind; another hope as its great end. If the past had never been between us,” said the woman, looking mildly, but with steadiness, upon him, “tell me, would you seek me out now? Ah, no!”

He seemed to yield to the justice of this supposition in spite of himself. But he said with a struggle, “You think not.”

“I can hardly think otherwise,” she answered. “Heaven knows! How can I believe that you would choose me when I can see that there is one who you weigh every female against? Choose her; do not know the repentance and regret I did. Whatever happens, I am hopeful that we will remain friends.”

She lifted her wine glass and toasted, “May you be happy with the one you love!”

Darcy remembered that he felt some inner turmoil, for he had not yet been ready to acknowledge the truth of her statements. But almost as if it acted of its own accord, Darcy’s hand lifted the wine glass in an answering salute.

He turned upon the Ghost and saw that it looked upon him with a questioning face.

“Interesting, is it not, that some can see so clearly, while others blind themselves to truth?” asked the Spirit. Darcy looked at himself calming sipping wine. A year ago he would have smugly thought that the woman he wanted to marry would return his sentiments. He had been in dire need of the comeuppance Elizabeth had delivered.

As if the Spirit read his thoughts, he was in the drawing room at the Hunsford parsonage.

“Spirit!” said Darcy. “Please, show me no more! Conduct me home. Do you delight in torturing me?”

“Only one shadow more!” exclaimed the Ghost.

“No more!” cried Darcy. “No more. I do not wish to see it. Show me no more!”

But his words were in vain, for he could hear himself exclaim, “In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.”

Darcy listened as he made avowals of all that he still and had long felt for Elizabeth. He could hear how he spoke on the subject of his sense of her inferiority—of its being a degradation—of the family obstacles which judgment had always opposed to inclination—all were dwelt on.

Darcy heard himself conclude by representing to her the strength of his attachment, which, in spite of all his endeavors, he had found impossible to conquer, and expressing his hope that it would now be rewarded by her acceptance of his hand. As he said this, Darcy cringed beside the Spirit, for he could easily see that he had no doubt of a favorable answer. He spoke of apprehension and anxiety, but his countenance expressed security. Such a circumstance could only exasperate Elizabeth, he now knew. Yet it was like being cut by a knife to hear rejection again.

“Spirit,” said Darcy in a broken voice, “remove me from this place. There was no need to bring me here, madam, for not a word, not a syllable have I forgotten. Do you wish to hear for yourself?” Darcy began to recite along with Elizabeth each and every word of her rejection. Not one word was spoken out of place.

“You could not have made me the offer of your hand in any possible way that would have tempted me to accept it. From the very beginning, from the first moment I may almost say, of my acquaintance with you, your manners, impressing me with the fullest belief of your arrogance, your conceit, and your selfish disdain of the feelings of others, were such as to form that ground-work of disapprobation, on which succeeding events have built so immoveable a dislike; and I had not known you a month before I felt that you were the last man in the world whom I could ever be prevailed on to marry.”

As the last word fell, Darcy turned on the Spirit with such a mixture of anger, bitterness, and despair, that she took a step away from him. “I told you these were shadows of the things that have been,” said the Ghost. “That they are what they are, do not blame me!”

“You have said quite enough, madam.” It was as if Darcy was speaking to both Elizabeth and the Spirit. “I perfectly comprehend your feelings, and have now only to be ashamed of what my own have been. Forgive me for having taken up so much of your time, and accept my best wishes for your health and happiness.”

“Leave me! Take me back. Haunt me no longer!”

The Ghost took a step away from him and then another, her light getting fainter, and repeated, “That the shadows are what they are, do not blame me!” each word further diminishing her light and appearance. Darcy observed a final burst of light that was burning so high and bright that he was forced to close his eyes.

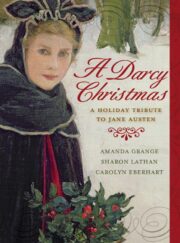

"A Darcy Christmas" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Darcy Christmas". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Darcy Christmas" друзьям в соцсетях.