“But you might have the baby on the way!” he said.

“And I might not,” she replied.

“We might be in a lonely spot, with no midwife to hand, and nothing but the coach to shelter you,” he protested. “No hot water, no maids, no Mrs. Reynolds. No, Lizzy, it will not do. I am sorry, my love, but I forbid it.”

Instead of meekly obeying his command, Lizzy’s eyes sparkled and she said, “Ah! I knew how it would be. When we were newly married, you would deny me nothing, but now that a year and more has passed, you are showing your true colours and you expect me to obey you in everything!”

“I doubt if you have ever obeyed anyone in your life,” he returned, sitting back and looking at her with a smile playing about his lips.

“No, indeed I have not, for I have a mind of my own and I like to use it,” she said. “Otherwise, it might grow rusty with neglect.”

He laughed. But he was not to be so easily talked out of his fears.

“Only consider—”

“I have considered!” she said. And then, more seriously, “Believe me, I have. I have scarcely ventured beyond the flower gardens these past few weeks and for the last sennight I have barely set foot out of the door, but I cannot do so forever. It is very wearing and very tedious. Mama’s first child was three weeks late, and if I am the same, there will be plenty of time for us to go and see Jane’s baby and still return to Pemberley before our baby is born. And besides, I want a family Christmas.”

“Then let us invite your family here.”

“No, it would not do,” said Lizzy, sitting down again. “Jane and the baby cannot travel. Besides, it is already arranged that the family will visit Jane’s new residence, Lowlands Park. Jane’s housekeeper has been preparing for the event for weeks. The rooms have been aired, the larder stocked, and the beds made up.” She took pity on him and said, “Jane’s new house is not so very far away. If we leave Pemberley after lunch we will be there in time for dinner, scarcely time for anything to happen. I promise you, if I feel any twinges before we set out then we will delay the journey.”

“And what if you feel a twinge when we are halfway to Jane’s?”

“Then we will carry on our way and I will be well looked after as soon as we arrive.” As he still looked dubious, she continued. “You know what the midwife said: ladies in my condition must be humoured, and my mind is made up,” she told him.

Even before their marriage, Darcy had learnt that Elizabeth had a strong will, so that at last, he conceded to her wishes.

“Then I had better let them know in the stables, and you had better tell Mrs. Reynolds that we intend to leave tomorrow. There will be a great many arrangements to be made if you are to have a comfortable journey.”

“Thank you, my dear. I knew you would see sense!”

He made a noise which sounded suspiciously like harrumph, and Elizabeth returned to her letters.

“Is there any other news?” he asked.

Elizabeth opened a letter from her mother and began to read it to herself. Every now and again she broke out to relate some absurdity.

Darcy, now that he was at a safe distance from Mrs. Bennet, found that he could enjoy her foibles.

“She thanks me for my letter,” said Elizabeth. Then she said, “Oh dear! Oh no!” She shook her head. “Poor Charlotte!”

Darcy looked at her enquiringly and she read aloud from her letter.

“Charlotte Lucas—although I should say Charlotte Collins, though why she had a right to Mr. Collins I will never know, as he was promised to you, Lizzy—called on us last Tuesday, for you must know that she and Mr. Collins are staying at Lucas Lodge. I saw at once what she was about. As soon as she walked in the room she ran her eyes over your father to see if he showed signs of illness or age. I am sure she will turn us out before he is cold in his grave. Thank goodness you have married Mr. Darcy, Lizzy, so that when your father dies we can all come and live with you, otherwise I do not know what we should do. My sister in Meryton does not have room for all of us, nor my brother in London, but at Pemberley there is room to spare—”

“Then we must hope your father lives to a ripe old age!” interposed Darcy.

Elizabeth laughed. “I am sure he will.” She began to read again. “We are setting out for Jane’s tomorrow and we mean to travel by easy stages, arriving on the 19th.” She broke off and said, “So they will be there in two days’ time. If we leave tomorrow then we will have Jane and the baby to ourselves for a day before Mama arrives.”

She finished reading the letter to herself, then told him what it had contained, shorn of her mother’s ramblings.

“Maria Lucas is going to Jane’s as well. She and Kitty have become firm friends and so Jane has invited her to keep Kitty company. I am glad of it. Mary is not much of a companion, as she spends her time either practising the pianoforte or reading sermons and making extracts from them. With Jane and I living our own lives and Lydia in the north, it must be lonely for Kitty.”

“Your mother will no doubt find a husband for her before too long,” said Darcy.

“I rather believe that is what she is hoping for this Christmas. There will be no other guests staying in the house, only family, but Mama hopes there will be entertainments in the evenings and visitors during the day, and that one of them might suit Kitty.”

“But only if he has ten thousand a year!”

“Yes,” said Lizzy. “You have quite spoilt Mama for other men!”

“Or at least, for other fortunes!” said Darcy.

“And now I must go and see Mrs. Reynolds, then in an hour, you must take me round the park in the phaeton.”

Elizabeth left the room and Darcy finished his breakfast, then went out to the stables where he gave orders for the journey on the following day. As well as the usual instructions, he made it plain that he required one of the under grooms, a lad who was an expert horseman and a very fast rider, to be amongst the party and that he expected the lad to ride Lightning. This produced a startled reaction from the head groom, for Lightning was one of the most expensive horses in the stables. But Darcy was adamant. Although he did not say so, he wanted to be sure that help could be brought quickly if Elizabeth unexpectedly went into labour.

At the mere thought of it, he almost decided to cancel the journey after all, but he knew it would give Elizabeth such pleasure that he could not deny her the treat.

On leaving the stables he returned to the house and went upstairs to speak to his valet. As he did so he passed the foot of the stairs leading to the second floor, wherein lay the nursery, and on a sudden impulse he mounted them.

They gave way to a corridor which was looking bright and cheerful, having been newly renovated. The windows had been cleaned and the view they gave over the Pemberley park was beautiful. Sweeping lawns spread in every direction, and beyond them lay the Derbyshire moor.

He trod on the squeaking floorboard and smiled. Elizabeth had at first wanted to replace it, but she had relented when he had told her that it reminded him of his childhood. When he had slept in the nursery, its sound had heralded the approach of visitors.

His had been a happy childhood, roaming the grounds and climbing trees, loved by both parents, his beautiful mother and his austere father. From his mother had come open demonstrations of affection; from his father had come a solid feeling of security.

“The Darcys have lived at Pemberley for over two hundred years,” his father had said to him. “It is a name to be proud of.”

And he had been proud. Too proud on occasion, he thought uncomfortably, as he remembered his early relationship with Elizabeth. But she had taught him that too much pride led to incivility and, worse, blindness. Blindness to the qualities of others, regardless of their rank. And so he had mended his ways, and in doing so he had won his dearest, loveliest Elizabeth.

He paused on the threshold of the nursery. It had been decorated in a sunny yellow and the window seat had been upholstered in a matching fabric decorated with rocking horses. The inspiration had been his old wooden rocking horse, which had been freshly painted and varnished. He had spent many happy hours playing on it, as he had spent many happy hours kneeling on the window seat and looking out at the gardens, his excitement brimming over as he had seen his first pony standing below.

He turned to look at the cot in which he himself had slept, and he had a sudden memory of his mother bending over him illuminated by a halo of light coming from the candles on the landing behind her. He could almost hear the swish of her brocade dress as she bent over him, and feel the soft fall of powder on his cheek as she kissed him goodnight.

And then the memory faded and he thought that here, soon, his own child would be sleeping, climbing on the window seat, riding on the rocking horse.

He had always known he must marry and provide an heir for Pemberley, but with Elizabeth it was so much more than that. It was not just marrying and then having done with it; it was going through life together, exploring its new experiences side by side. And it was this, having a child together, becoming a family.

He smiled and, with one last look around the room, he went down to the first floor. He gave instructions to his valet for the morrow, then he went downstairs and rang for Mrs. Reynolds.

“Mrs. Darcy has no doubt told you of our plans for tomorrow,” he said.

“Yes, sir, she has.”

“I want to make sure that everything is done for her comfort. Blankets in the coach, a hot brick for her feet, a hamper of food with some tempting delicacies, and plenty of cushions.”

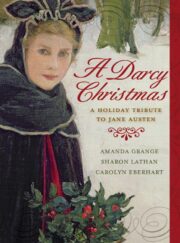

"A Darcy Christmas" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Darcy Christmas". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Darcy Christmas" друзьям в соцсетях.