He saw Elizabeth nod from the window. Eagerly, he strode into the garden.

Elizabeth was filled with gladness when she saw Darcy arrive. When he silently asked to be met in the garden, she could only nod, for the rest of her seemed frozen in place. Only when she saw him stride away did she regain movement. She began to move to the door.

“Where do you think you are going?” Mrs. Bennet asked.

“I am going for a walk in the gardens. The room is overheated and a walk would do me some good.”

“It would do you some good to stay and talk with Mr. Topper. He has almost three thousand a year! And he has shown an interest in you!” cried Mrs. Bennet.

Curious, Bingley looked out the window, and recognizing the horse his groom was leading away, said, “I do believe some fresh air would do you a world of good, Elizabeth.” He quickly made his way to the door and opened it for her.

“I hope so, Charles, I hope so,” replied Elizabeth, as she left the room. Outside the room she raced down the stairs and ran down the hall to the doorway, only skidding to a halt when she saw a footman with her cloak, gloves, and bonnet. Hastily putting on these outer garments, she hurried into the garden where Darcy was waiting and pacing.

“Miss Bennet.” They were the only words he could get out of his mouth. Elizabeth was also stricken with silence. Darcy offered his arm, Elizabeth took it, and they began to walk in silence.

When they came upon a sheltered bench, they stopped and sat down. Elizabeth looked down at her clasped hands, until Darcy covered her hands with his. Then she looked up into his eyes, his bright, shining eyes that held a touch of shyness, determination, and another emotion that she was afraid to name.

“Miss Bennet, last April you said that I could not have made you the offer of my hand in any possible way that would have tempted you to accept it. Even if your answer remains the same as it was then, please allow me to speak a second time upon this subject.”

“As you wish.”

“Miss Bennet, few people get to see into the future and what joys or calamities may be waiting there. Last night I was fortunate to get a glimpse of my future. I do not know if it was a dream or a vision, I only know that the future that lay before me was bleak and stark and lonely because you were not in it.”

Elizabeth knew from the look in his eyes that he was telling the truth.

“So I am asking you to share the future with me, to change that wretched existence I saw into a one of great joy and happiness. I love you. I shall always love you. I am willing to wait with a hope that someday you will return my regard. Please say that I may have some hope.”

“You may, for it would not be a very long wait,” said Elizabeth. “Not long at all.”

“Dearest, loveliest Elizabeth, would you do me the very great honor of accepting my offer of marriage?”

Elizabeth, feeling all the common awkwardness and anxiety of the situation, now forced herself to speak. “I wish you to understand that my sentiments have undergone so material a change since that time, that your present assurances fill me with gratitude and pleasure and the only answer I can give is… yes.”

The happiness that this reply produced was such as he had never felt before, and he expressed himself on the occasion as sensibly and as warmly as a man violently in love can be supposed to do. “Thank you,” he raised her gloved hands to lips and kissed each one. “Thank you, I will endeavor to make sure you never have cause to regret your decision.”

Had Elizabeth been able to encounter his eyes, she might have seen how well the expression of heartfelt delight diffused over his face became him; but, though she could not look, she could listen, and he told her of feelings which, in proving of what importance she was to him, made his affection every moment more valuable.

“You are cold,” he noticed and was immediately concerned. “Let us return to the house so that you can be warmed.”

Elizabeth shook her head. “No, it is too soon to return to others, to be amongst them. Let us walk for a bit; that will take off any chill.”

So they walked, without knowing in what direction. There was too much to be thought and felt and said for attention to any other objects.

“I should not have waited so long to come to you. Last fall, I had a visit from my aunt, who called upon me in London, and related her journey to Longbourn, its motive, and the substance of her conversation with you, peculiarly denoting your perverseness—her words—as she sought to obtain that promise from me, which you had refused to give. But, unluckily for her ladyship, its effect had been exactly contrariwise. It taught me to hope,” said he, “as I had scarcely ever allowed myself to hope before. I should have come then.”

“Why did you not come? Surely you knew enough of my disposition to be certain, that had I been absolutely, irrevocably decided against you, I would have acknowledged it to Lady Catherine, frankly and openly.” Elizabeth colored and laughed as she continued, “After abusing you so abominably to your face, I could have no scruple in abusing you to all your relations.”

“Fear, doubt, pride. My aunt can be quite overbearing, and I feared you simply would not provide her the satisfaction of giving her the assurance she demanded. Your previous refusal has weighed heavily on my mind. I was doubtful that even if your feelings for me had changed for the better, they may not have been strong enough to accept a proposal, and I felt my pride could not withstand another rejection, no matter how gently or kindly given.”

“And I had not treated your feelings so kindly in the past.”

“My behavior to you at the time merited the severest reproof. It was unpardonable. I cannot think of it without abhorrence and was doubtful that you could ever forgive me.”

“We will not quarrel for the greater share of blame annexed to that evening,” said Elizabeth. “The conduct of neither, if strictly examined, will be irreproachable. But since then we have both, I hope, improved in civility.”

“I cannot be so easily reconciled to myself. The recollection of what I then said—of my conduct, my manners, and my expressions during the whole of it—is now, and has been for many months, inexpressibly painful to me. Your reproof, so well applied, I shall never forget: ‘Had you behaved in a more gentlemanlike manner.’ Those were your words. You know not, you can scarcely conceive, how they have tortured me, though it was some time, I confess, before I was reasonable enough to allow their justice.”

“I was certainly very far from expecting them to make so strong an impression. I had not the smallest idea of their ever being felt in such a way.”

“I can easily believe it. You thought me then devoid of every proper feeling; I am sure you did. The turn of your countenance I shall never forget, as you said that I could not have addressed you in any possible way that would induce you to accept me.”

“Oh! Do not repeat what I then said. These recollections will not do at all. I assure you that I have long been most heartily ashamed of it.”

“My letter, did it,” asked Darcy, “did it soon make you think better of me? Did you, on reading it, give any credit to its contents?”

She explained what its effect on her had been: “My feelings as I read your letter can scarcely be defined. With amazement did I understand that you believed any apology to be in your power; and I was steadfastly persuaded that you could have no explanation to give that would be acceptable. It was with a strong prejudice against everything you might say that I first read your letter,” Elizabeth was embarrassed to confess.

“Your belief of Jane’s insensibility I knew to be false. Your account of the real and the worst objections to the match made me too angry to perceive any justice in your words.” Elizabeth gave Darcy a wry little smile. “And it was some time, I confess, before I was reasonable enough to allow their justice. As to Mr. Wickham, every line proved more clearly that in matters between you and him, you were entirely blameless throughout the whole, which I would have believed to be impossible before reading your letter.”

Darcy wanted to offer her some comfort, but Elizabeth spoke before he could do so. “I was absolutely ashamed of myself. I had been blind, partial, prejudiced, and absurd. It was a hard realization to face, for I had prided myself on my discernment!” Elizabeth shook her head at her folly.

“I knew,” said he, “that what I wrote must give you pain; but it was necessary. I hope you have destroyed the letter. There was one part, especially the opening of it, which I should dread your having the power of reading again. I can remember some expressions which might justly make you hate me.”

“The letter shall certainly be burnt if you believe it essential to the preservation of my regard; however, though we both have proof that my opinions are not entirely unalterable, they also are not, I hope, quite so easily changed as that implies.”

“When I wrote that letter,” replied Darcy, “I believed myself perfectly calm and cool; but I am since convinced that it was written in a dreadful bitterness of spirit.”

“The letter, perhaps, began in bitterness; but it did not end so.” Elizabeth stopped to look at him. “The adieu is charity itself. But think no more of the letter. The feelings of the person who wrote it and the person who received it are now so widely different from what they were then that every unpleasant circumstance attending it ought to be forgotten. You must learn some of my philosophy. Think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure.”

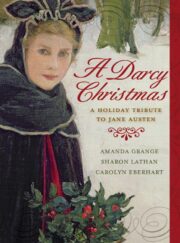

"A Darcy Christmas" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Darcy Christmas". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Darcy Christmas" друзьям в соцсетях.