But what of Mr. Dillman? Who killed him? Surely not the same person who’s responsible for the paint? Why would he have bothered with the paint at all if he were planning to kill the man? My mind reels trying to figure it out. Emily’s so quick when it comes to these things. I’m glad no one has to rely on me for finding the answers.

Except this answer. Are some sins so great they merit execution rather than exposure? Is that why Mr. Dillman died? And if so, what makes a sin that heinous? Could mine be considered so?

I fear even to write these words in my happy home, where my daughter, so innocent, plays. I don’t want to bring such ugliness to her world. How I wish I could hide forever from what I’ve done.

12

Once Colin was satisfied we’d gathered everything useful we could from the Royal Academy, he headed for Scotland Yard while I set off on an errand of my own. I was worried about Cordelia Dalton and had made a point of calling on her every few days since her fiancé’s death. The Daltons’ house was quiet and dark when I arrived—too many closed velvet curtains—and a servant set off to fetch Cordelia from her bedroom. The poor girl was like a prisoner. When she entered the gloomy sitting room, I hardly recognized her. Her dress hung on her—she must have lost a stone in the past weeks—and her face, gaunt and dull, looked ten years older than when I’d seen her last.

“Cordelia!” I could not help leaping up and embracing her. “How are you managing?”

She didn’t say anything, but twisted and twisted her black-hemmed handkerchief.

“Has something happened?”

“No. No. Not a thing.” She twisted harder. “Would you like tea? Ivy was just here, but she didn’t want any. She’d be sorry to have missed you.”

“I don’t require any tea, thank you,” I said. I could see she was biting the inside of her cheek. “Are you quite sure nothing else has happened? Please, Cordelia, my husband and I can’t help you if you don’t keep us au courant of the situation.”

She burst into tears and collapsed onto a settee. I sat next to her and put a hand on her back, rubbing softly.

“Have you received another letter?” I asked.

“Three,” she managed to gasp between sobs.

“Three?” I did my best to hide the chagrin I was feeling. Making her feel worse wouldn’t help at all.

“I wanted to tell you. I did. Truly,” she said, keeping her head buried in her hands. “But he insisted I couldn’t. Said if I informed anyone he’d kill my mother.”

Now I was angry, but not at Cordelia. How dare this person torment her so?

“What else did he say?”

“In the first, he chastised me for not coming to the meeting he’d demanded. Do you remember?”

“Yes,” I said. Colin and I had told her in no uncertain terms not to even consider going to the park in such circumstances.

“In the second, he said how important it was that I do what he tells me and that I not share any of what he wrote with anyone else or the consequences, as I explained, would be dire. The third came yesterday. He’s insisting upon meeting me tonight, and says that if I don’t succumb to his wishes untold evil will befall me.”

“It sounds as if his imagination has failed him,” I said. “Where does he want you to go?”

“The same place. Achilles.”

“You’re not to go,” I said.

“But he’ll—”

“Stop, Cordelia. Think carefully. This man has already killed once. He believes you to be in possession of something that could harm him, some evidence that he wants you to return to him, correct?”

“Yes.”

“You don’t know what it is?”

“No.” Her voice was small.

“So what would you do if you met him? Give him nothing? What would he do to you then?”

“We could invent something … something I could give him to satisfy his wishes.”

“We have not even the vaguest notion of what that would be. Unless you’re hiding something from me?”

“No, I swear I’m not.” She started to cry again. “I’ve already told you everything and now he’ll—”

“He won’t do a thing. Mr. Hargreaves wouldn’t allow it.” We did have to do something, but I wasn’t sure what. “So long as this man believes you are in possession of this information, he won’t harm you. If he did, he’d have lost his way to recover it.”

“But if I do nothing—”

“You cannot go. Don’t even consider it. How would you even get out of the house? Your father would never allow it.”

“He would if he thought my mother was in danger.”

“I’ll go in your place,” I said. “And I’ll take Colin with me. We’ll confront whoever is there—I doubt it will be the man himself—and do whatever it takes to stop you from suffering further torment.”

“Do you really think it would work?” she asked.

“I’m absolutely confident.”

She seemed to believe me.

If only I could convince myself.

Colin was less put off by my scheme than I’d expected. He read the letters—Cordelia had let me take them—and agreed we had few other viable options. The meeting was scheduled for ten o’clock, a time when almost no one would be in the park. Thankfully, it would still be light out, but nonetheless, I felt slightly nervous about the undertaking. With Meg’s help, I put on one of the mourning dresses I’d stored away years ago and fixed a black veiled bonnet to my head. It was unlikely anyone who knew Cordelia would mistake me for her, but if our villain had sent someone in his stead, it was possible I could pull off the deceit.

Colin left the house well ahead of me, dining at the Reform Club instead of at home, to confuse anyone who might be watching us. He would make his way to the park early, and set himself up in a hiding place well before I—or our adversary—would arrive. Cordelia would have taken a carriage from her house, so though it was somewhat ridiculous to drive so short a distance, I did it nonetheless, taking two footmen with me. One of them I brought with me to the sculpture while the other waited at the gate to the park. There was no one else in sight.

“That’s fine, leave me here and go back to the gate,” I said to my loyal servant. “This miscreant can’t expect a lady to come out at night completely unescorted.”

He did as he was told and I stood, alone, at the base of the hulking statue George III had installed to honor the Duke of Wellington’s numerous victories in the Napoleonic Wars. It had caused a furor when first erected earlier in the century, a furor that stopped only when a strategically placed fig leaf was added to the piece, giving the Greek hero—I use the term loosely—a more socially acceptable appearance. Not even Achilles was above the vexation of society.

I kept my back to the sculpture, not wanting to leave myself more exposed than necessary, and waited, wondering where Colin was sequestered. I checked my watch. It was nearly ten o’clock, and there was no sign of anyone coming to meet me. I smoothed my heavy skirts, remembering what it had been like to wear them daily, all those years ago, after the death of my first husband.

I started, thinking I’d heard footsteps, but could see no one approaching. My heart pounded, but I knew I was safe under Colin’s watchful eye. Knowing and feeling are two different things, though, and my nerves were not soothed by the confidence my head had in my husband. I looked around, searching for any hint of where he might be hidden. His options seemed limited, unless he’d been willing to climb a tree. I found no evidence of him. Not that I would have expected otherwise.

My vigil continued. Then, in the distance, I saw a woman coming towards me. She was walking up the path from the south, which meant she’d not entered the park through the Achilles Gate as I had done. At first, she was a mere wisp of a figure. I could almost believe I was imagining her. As she came closer, though, she scared me. Her boots fell heavy on the ground, despite the fact she was a small woman, a good six inches shorter than I and painfully thin. She looked to be about my age, but the years were written harder on her face than mine. Her mouth was pinched, her nose ordinary, but her eyes, brown and luminous, shone like unearthly gems. She faltered as she approached, reached a hand into the pocket of her coarse skirt, and pulled out a note, which she shoved towards me.

I reached out and took it from her.

The handwriting matched the notes Cordelia had received.

In turn, I handed the girl the letter we’d had Cordelia write in response to her correspondent’s unwanted attentions:

I should like nothing more than to offer you whatever necessary to drive you away from me. But, alas, Mr. Dillman left nothing for me that would satisfy your needs. Furthermore, he never spoke of any involvement with a person such as yourself, and I find myself quite at a loss as to what to do. Please leave me alone.

The girl pulled the envelope from me roughly and glared at me. She did not open it.

“How does he keep hold on you?” I asked. “Does he threaten you? Is he cruel?”

She did not reply.

“Come with me,” I said. “We can help you break free from him.”

She gave no response, made not even the slightest change in her expression. It was as if she didn’t comprehend my words. I tried again, this time in French.

And then in Italian.

And then in my extremely bad German. Which, to be fair, few people would have been able to understand.

Before I resorted to ancient Greek, my attention was diverted by a loud crash coming from behind me. Without thinking, I spun around, and then turned back. The girl remained expressionless.

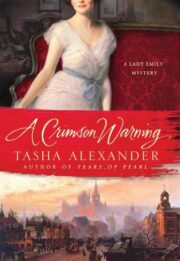

"A Crimson Warning" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Crimson Warning". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Crimson Warning" друзьям в соцсетях.