“It’s beautiful,” I said.

“But you wouldn’t have the courage to wear it.”

“Not outside a fancy dress party,” I said, taking a seat in a low, gilded chair before I noticed we were not alone in the room. Reginald Foster, resplendent in a perfectly tailored jacket, was standing on his tiptoes to greet me. “Mr. Foster! Forgive me, I didn’t see you.”

“No apology necessary. Who could focus on anything beyond the beauty in front of us?”

“You appear to be in the wrong room, Mr. Foster,” I said. “Lady Glover, do you have a designated space for medieval courtly love?”

“What an idea!” She pushed up one elbow and rested her chin on her hand. “I should redo the entire house, making each room reflect a different historical period.”

“Just don’t have a Waterloo room,” Mr. Foster said, masterfully dividing his glances equally between us two ladies. “Apsley House should have the exclusive rights to that. The Duke of Wellington deserves nothing less.”

“Fair enough,” she said. “But I am going to have a room whose walls are covered in red paint.”

“Do you think that’s wise?” Mr. Foster said. “The perpetrator is wreaking havoc on society.”

“Which is just what society deserves,” she said. “Come now, Reggie, you cannot claim you don’t agree with me. We’ve discussed this too many times.”

“I do appreciate how passionately you feel about the subject, Valerie, but there must be limits,” he said, his voice softer than it had been. “You know that perfectly well. We can’t have the public acting as vigilantes. It would lead to no end of trouble.”

“You’re lucky you’re not my husband, Reggie,” she said. “I’d force you to openly support my positions.”

Their easy familiarity with each other took me aback. I couldn’t decide whether to be impressed or shocked that a man with Mr. Foster’s political aspirations could openly associate with a woman of Lady Glover’s reputation.

Without pausing or giving the slightest reaction to her comment, Mr. Foster changed the subject. “You told me Lady Emily is aware of the correspondence you received regarding the matter at hand?”

“Lady Emily was the first person in whom I confided. Proximity to her husband is nearly the same as being an agent for the Crown, you know.”

“I’ve been trying—with no success—to convince Lady Glover to tell me what she sent this madman in reply,” Mr. Foster said. His voice had lost the intimate tone that had crept in earlier, and he sounded more like a politician again.

“I wouldn’t count on getting her to crack,” I said. “You’ll have to satisfy yourself with the content of the note she received.”

“And the yellow sealing wax,” Mr. Foster said. “One doesn’t see that often.”

“You were here when Lady Glover opened the note?” I asked.

“No, no, I only just read it before you arrived,” he said.

“Our man was clever to leave no clue to his identity,” Lady Glover said.

“Or so it would seem. I wonder his motivation is for sending it at all? What can he hope to gain?” I asked. “May I read it again, Lady Glover?” She handed it to me and I analyzed every inch of the page. There was an oily stain where the wax had once been, but no trace of it remained.

“I think it may be your friend, Mr. Barnes, who is reaching out to me,” Lady Glover said, leaning closer to Mr. Foster. “He’s an outsider, as am I, and might rightly suspect I’d lend a sympathetic ear to his plight.”

“That, my dear, may be the silliest thing you’ve ever suggested,” Mr. Foster said. “Simon isn’t an outsider. He’s nearly as important to this country as the prime minister.”

“He’s not English,” Lady Glover said.

“A fact that hasn’t curtailed his influence on those who run the empire,” Mr. Foster said. “You won’t find a better respected man in Westminster.”

“He’d say the same thing about you,” I said.

“He’s been splendid to me since school. I was a few years behind him and he took me quite under his wing during my first days. He remembered what it was like to be the new boy. I’d trust him with my life.”

“I admit that’s something of a relief,” Lady Glover said. “He’s not my vision of a romantic correspondent.”

“I don’t see how there’s anything romantic about receiving correspondence from a murderer,” I said. “You should take this very seriously, Lady Glover.”

“I assure you, I do,” she said. “I shall set Lord Glover to the task of having the house watched. I want to know who is delivering these messages.”

“It was only one message, was it not?” I asked. “What makes you think there will be more?”

“My dear Lady Emily,” she said. “More are a certainty. I’m in my element here. You can trust me to know when a man will be back in contact.”

11

For years, Ivy and I had made a habit of meeting for a morning ride in Rotten Row, and it had long ago become one of my favorite daily rituals during the season. The morning light would fall soft on leaves and grass and make a glowing cloud out of the dust kicked up by our horses’ hooves. We would start off slowly, then I’d pull ahead, goading her to race. She’d protest, worried we’d shock society and horrify the multitudinous other riders. But soon enough she’d be following me, pulling up close, and egging me on.

Today, I regretted not having had more than a small piece of toast and a single cup of tea to fortify me before I’d set off. I hadn’t realized Winifred Harris would be joining us, or just how much fortification dealing with her could require. It took fewer than ten minutes for me to confirm something I’d long suspected: try though I might for Ivy’s sake, Winifred and I would never be close. Our conversation was stilted from the outset, and she scolded me fiercely the second my horse started to move a beat faster than a canter, explaining to us in overwrought detail how inappropriate our previous behavior had been.

“Furthermore, it’s not good form,” she said, just as I’d started to hope she was nearly done. “It’s dangerous, too, as there are so many riders present. But most of all, think of the talk to which it has exposed you. Do you want to draw ire upon yourselves? Do you want to be left off guest lists because you’re considered wild?”

Personally, I was quite taken with the notion. No one had ever suggested to me before that I might be wild. It seemed something to which one might aspire.

“Thank heavens we’re both already married,” I said, knowing my irony would be completely lost on Winifred. “We’d be scaring off every potential husband we met.”

“I don’t mean to be stern with you,” Winifred said, puffing up her broad chest. “Please understand that. But it’s essential we stay vigilant in the protection of our characters. What does a lady have that matters more than her reputation?”

“I can think of lots of things,” I said, but wasn’t allowed to continue.

“One need only look at how Lady Merton’s circle has shrunk since her house was painted. Consider that, Lady Emily, and then consider your connection with the Women’s Liberal Federation. It’s very off-putting,” she said. “People are beginning to talk.”

“Let them,” I said. “I believe in what I’m doing.”

“You’re just trying to get attention. No thinking person can believe women should have the vote. It’s a revolting concept. You should know your place better than that.”

“You know, Winifred, you begin to make me wonder if all women should have the right to vote.”

My insult was lost on her as her attention was elsewhere. “Look at that! Her posture is appalling!” She pulled closer to Ivy and motioned with a subtle gesture to indicate a rider not far from us, but made no attempt to modulate her voice. “Did you see her at the opera last week? Her gown was atrocious and her manners even worse.”

“She is kind, though,” Ivy said. “Her younger sisters adore her.”

“Precisely,” Winifred said. “She’s a good woman, yet she doesn’t bother to care what impression she makes. Which means she has nothing in store but ruin and loneliness. If she’s fortunate, she’ll find a post as a governess.”

I kept silent.

“I can tell you’re angry at me for speaking so openly, Lady Emily. You think I’m hard on my own sex. But I feel the same about gentlemen. Do you see that man over there?” she asked. “An extremely well-known youngest son—there, standing on the pavement perpendicular to us, speaking to a woman in a garish purple hat? I understand his gambling debts are close to ruining his entire family. What sort of a man allows himself to sink to such a level?”

“Isn’t it enough for him to live with what he’s done?” I asked.

“I know how high the standard to which you hold yourself is, Winifred dear,” Ivy said. “But not everyone is so capable as you.”

“We must learn from the mistakes of others, Ivy,” Winifred said. “That is the only reason I condone paying attention—close attention—to what is happening in the private lives of others.”

“Private lives should be just that,” I said, unable to hold my tongue any longer. “No good comes of spreading gossip.”

“Emily, you can’t possibly mean to accuse me of being a gossip!” Her eyes opened wide. “I make these observations only to help my friends because I care about them so deeply. I see all around me the tragedies that can befall those who are not vigilant, and only want to protect those dear to me from suffering a similar fate.”

“What an interesting position,” I said, realizing the futility of arguing with someone like Winifred. “What do you think, then, of this person terrorizing society with his red paint?”

“I cannot approve, of course,” she said. “But I think we’d all have to admit he’s catalyzed a welcome change in people’s behavior. Who will embark on a bad course of action when he knows he might face exposure and censure?”

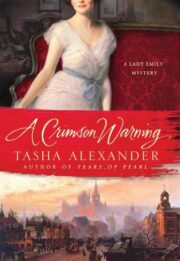

"A Crimson Warning" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Crimson Warning". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Crimson Warning" друзьям в соцсетях.